One of the main critiques I hear about my writing time and time again is that I just keep talking. I may not even go off on long tangents, but I still somehow manage to lose my reader. I will have some great and meaningful idea, but it inevitably becomes lost in too many words and phrases, the cloud of smoke from me literally just spinning my wheels. Even now I probably could have just left it at the first sentence and been done. In the end, whatever idea I was trying to convey is buried away and lost and whatever my reader concludes from my work is left to a variety of factors, most influential being themselves.

Here is an ordinary maze.

(Eddins, Solving mazes with the watershed transform)

You look at it and at first it all seems to blend into one gray block. Then, as you look at it longer, you see the individual pathways it is comprised of. Longer still you form routes that lead you somewhere, hopefully to the end, but mostly just to a three sided failure. How do we decide which path to take when we come to each split?

In the story of “The Library of Bable”, the librarians are faced with a maze of a different kind. Shelves upon shelves of books each contain some combination of letters as to amount to be comparable to a maze of near infinite area. The library is massive, but, like the real universe, much of it is empty only in a different sense: “For every rational line or forthright statement there are leagues of senseless cacophony, verbal nonsense, and incoherency” (Borges, 1998, p. 114). More specifically it is devoid of meaning. If all of the books in the fictional library were reduced to only those that had actual meaning, only a small, infidecimal fraction would remain. Here is the first maze, or rather what is left of it after cutting away all of the dead ends and fruitless paths.

So much is actually devoid of meaning and it is in those meaningless sections that we lose are way, searching for something that is not there. These sections of the maze are construed in much the same way as how the librarians in Borges’ short story see the unlimited possible combinations of books, “Those phrases, at first apparently incoherent, are undoubtedly susceptible to cryptographic or allegorical ‘reading’” (1998, p. 117). We place significance in what is really unnecessary or false and thus lose the correct path to truth.

In a two dimensional puzzle, this disparity between the meaningful and insignificant can be easily overcome, but what happens when this occurs, as it so often does, in our real lives? Even more so, what happens when the path we must find is one that will lead us to our freedom? This is the fundamental question and challenge for the podcast Serial; the maze: the events of one day surrounding the murder of a high school girl, the target path: a mere window of only about half an hour, the finish: a final answer to a young girls mysterious death and possibly the release of a wrongfully committed man.

In the podcast, Sarah Koenig tasks herself with taking this maze and cutting away the meaningless and incorrect in much the same way as the librarians. Both seek out real truth, but each are faced with evidence that they must judge for merit. In the opening episode, Koenig explores the inconsistencies of memory. The witnesses are being asked to recall events from 15 years ago and in that time, most people tend to forget and then reconstruct the past. In the same way that a book in the library may claim to be truth through only the chance that arranged the letters, witnesses for the case claim at times completely different and contradictory sets of events.

While witnesses do lie to protect themselves or others or their imaginations fill in the missing pieces, we only believe them through our own folly. In a maze, if you simply step back and look ahead at the two paths, you will probably see that one dies out relatively quickly; however, we still charge ahead into the deceitful dead ends. We want to believe that one path looks easier or we think that it directs more towards the side of the finish, but these are all only what we want to see. Much like the librarians that search the library in search of validations, they search for what they want to find, ignoring the rest. This is a major problem for cases like the one considered in Serial, Koenig is so often searching for ways to prove the innocence of the convicted. While she does often consider the possibility of Adnan Syed’s, the possibly wrongly convicted murder, guilt, you become almost connected with him after having listened to him talk in interviews so much directly. In such a scenario like this where there is a multitude of evidence on both ends and such a haziness about what is real or not the attractiveness of the Librarians’ folly becomes relatable. The witnesses’ foggy memories, lies, and misinterpretations create the evidence that is “susceptible to cryptographic or allegorical ‘reading’” (Borges, 1998, p. 117). It is easy to want to favor one interpretation of events that fits your wants and so, in the end, we take an easier decision and possibly plunging into a dead end or false conclusion.

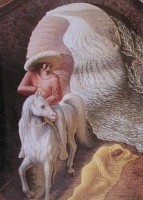

What we see Koenig or the prosecuting lawyers from the case doing is no different than the librarians seeking their validation. Each knows it sits out there somewhere on a shelf, possibly right in front of them, but they have to convince themselves as to its validity. Only the murder really knows the truth, he is the true “Book-Man” (Borges, 1998, p. 116). Our own biases affect what we see when we come to a point where we must interpret what is ahead of us; if we want to see something it will guide us when we come to a split in our maze. Consider this picture:

(Amazing Visual Illusions)

One reader sees an old man, the other a bridge and horse, possibly even a third or fourth interpretation appears to another. Who is right? You can be told one image is there but stare in vain for hours and never see it. Being blind to the possible, however, can lead you to success, but only through luck. More often our ignorance sends us down the path to assured failure: another dead end, a fabricated interpretation of meaningless characters, a false conviction. Someone that can see both images enables themselves to make a clear and educated decision of their own as to what they see, choosing to block out any confirmation bias they may develop. One can even decide to take the infidels’ claim that parts of what we see is “not ‘sense,’ but ‘non-sense’” (Borges, 1998, p. 117) and avoid leading ourselves astray altogether. It is through solid, balanced reasoning that we arrive respectively at the end of the maze and hopefully not through the trial and error of a lab rat.

The maze is not one straight line from start to finish, my writing is not a single explicit sentence, the library is not a single volume of books of fact, and neither is life. In the eye opening example of Serial, what we need to take away is not the literal, but the abstract. The path of the world is not clear cut, there are many disguised pitfalls and convincing illusions and so we must take events with a skeptical view so that we can find the true route to the finish.

Amazing Visual Illusions. (2012, February 30). Retrieved February 2, 2015, from www.funpedia.net/amazing-visual-illusions

Borges, J. (1998). The Library of Babel. In Collected Fictions (p. 114). New York, New York: Penguin Group.

Eddins, S. (Photographer). (2014, January 21). Solving mazes with the watershed transform [Web Graphic]. Retrieved from http://blogs.mathworks.com/steve/2014/01/21/solving-mazes-with-the-watershed-transform/

Snyder, J., & Koenig, S. (2014). Serial [Radio series]. Chicago, Illinois: This American Life.