One of the main critiques I hear about my writing time and time again is that I just keep talking. I may not even go off on long tangents, but I still somehow manage to lose my reader. I will have some good idea, but it inevitably becomes lost in a sea of words and phrases, the cloud of smoke from me literally just spinning my wheels. Even now I probably could have just left it at the first sentence and been done.

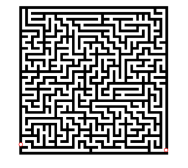

Take this maze for example,

(Eddins, Solving mazes with the watershed transform)

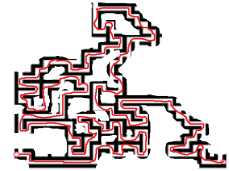

you look at it and at first it all seems to blend into one gray block. Then you look at it longer, you see the individual pathways. Longer still you form routes that lead you somewhere, hopefully to the end. In the story of The Library of Bable, the librarians are faced with a maze of their own. Shelves upon shelves of books each contain some combination of letters as to amount to be comparable to a maze of near infinite area. The library is massive, but, much like the universe, much of it is empty: “For every rational line or forthright statement there are leagues of senseless cacophony, verbal nonsense, and incoherency” (Borges, 1998, p. 114). More specifically it is devoid of meaning. If all of the books in the fictional library were reduced to only those that had actual meaning, only a small, infidecimal fraction would remain. Here is the maze, or rather what is left of it after cutting away all of the dead ends and fruitless paths.

So much is actually devoid of meaning and it is in those meaningless sections that we lose are way, searching for something that is not there. These sections of the maze often construed in much the same way as the librarians in Borges’ (1998) short story, “Those phrases, at first apparently incoherent, are undoubtedly susceptible to cryptographic or allegorical ‘reading’” (p. 117). We place significance in what is really unnecessary or false and thus lose the correct path to truth.

In a two dimensional puzzle, this disparity between the meaningful and insignificant can be easily overcome, but what happens when this occurs so often in our real lives? Even more so, what happens when the path we must find is one that will lead us to our freedom? This is the fundamental question and challenge for the podcast Serial; the maze: the events of one day surrounding the murder of a high school girl, the target path: a mere window of only about half an hour, the finish: a final answer to a young girls mysterious death.

In the podcast, Sarah Koenig tasks herself with taking this maze and cutting away the meaningless and incorrect in much the same way as the librarians. Both seek out real truth, but each are faced with evidence that they must judge for merit. In the opening episode, Koenig explores the inconsistencies of memory. Similarly to how one of the books may claim to be truth, witnesses for the case claim at times completely different sets of events. As the series progresses though, it becomes apparent that poor memory is not the only cause of false information.

While witnesses do lie to protect themselves or others, we only believe them through our own folly. In a maze, if you simply step back and look ahead at the two paths that lead ahead, you will probably see that one dies out relatively quickly; however, we still charge ahead into the dead ends. We want to believe that one path looks easier or we think that it directs more towards the side of the finish, but these are all only what we want to see. Much like the librarians that search the library in search of validations, they search for what they want to find, ignoring the rest. This is a major problem for cases like Serial, Koenig is so often searching for ways to prove the innocence of the convicted. While she does often consider the possibility of his guilt, you become almost connected with him after having listened to him talk so much directly. In such a scenario like this where there is a multitude of evidence on both ends and such a haziness about what is real or not, it is easy to want to favor one interpretation of events that fits your wants. In the end, we end up taking an easier decision and possibly plunging into a dead end or false conclusion.

The maze is not one straight line from start to finish, my writing is not a single explicit sentence, the library is not a single volume of books of fact, and neither is life. In the startling example of Serial, what we need to take away is not the literal, but the abstract. The path of the world is not clear cut, there are many disguised pitfalls and convincing illusions and so we must take events with a skeptical view so that we can find the true route to the finish.

Borges, J. (1998). The Library of Babel. In Collected Fictions (p. 114). New York, New York: Penguin Group.

Eddins, S. (Photographer). (2014, January 21). Solving mazes with the watershed transform [Web Graphic]. Retrieved from http://blogs.mathworks.com/steve/2014/01/21/solving-mazes-with-the-watershed-transform/